M1 GPUs for C++ science: SAXPY and finite differences

In this follow-up I want to look at a bit more practical uses for shaders written in the Metal Shading Language for scientific C++ code. I would like to end up at the point where we can comfortably use MSL combined with C++ to solve PDEs faster than we would on the CPU. To that extent, let’s see if we can get SAXPY and finite differences to work in MSL.

Sending off commands

In this previous post, we saw how to

create an object to keep track of all MSL parts: it contained multiple buffers for

arrays (MTL::Buffer, using a mode s.t. they were accessible from CPU and GPU), the

function pointers (pointers to MTL::Function) and pipelines (pointers to

MTL::ComputePipelineState), a command queue to pass instructions to the metal device

(MTL::CommandQueue) and a few functions that allowed us to roll up all the ingredients

of a calculation (i.e. buffers + functions/pipelines) and send them to the command

queue. Let’s have a bit more of a dive into the internals of running shaders on Metal

devices with this approach, to see how we can improve to run many different shaders from

one library.

The previous class we built, MetalAdder, used a method called sendComputeCommand()

to set off our kernel computation.

void MetalAdder::sendComputeCommand()

{

// Create a command buffer to hold commands.

MTL::CommandBuffer *commandBuffer = _mCommandQueue->commandBuffer();

assert(commandBuffer != nullptr);

// Create an encoder that translates our command to something the

// device understands

MTL::ComputeCommandEncoder *computeEncoder =

commandBuffer->computeCommandEncoder();

assert(computeEncoder != nullptr);

// Wrap our computation and data up into something our Metal device

// understands

encodeAddCommand(computeEncoder);

// Signal that we have encoded all we want.

computeEncoder->endEncoding();

// Execute the command buffer.

commandBuffer->commit();

// Normally, you want to do other work in your app while the shader

// is running, but in this example, the code simply blocks until

// the calculation is complete.

commandBuffer->waitUntilCompleted();

}

Internally, it does a few things:

- Retrieve a command buffer linked to the command queue. We need to place our GPU instruction into this buffer.

- Create a command encoder, an object that takes our buffers (

MTL::Buffer, those things that contain our actual data) and pipelines (basically computational instructions) and parses them to something our hardware understands. It turns out we can’t simply pusha+bto our command buffer. - Encode the add instruction and its buffers, for which we use another class function that we will get to.

- Signal that we encoded all we want (

computeEncoder->endEncoding()). - Signal that the command buffer can start sending its commands to the hardware

(

commandBuffer->commit()). - Wait until the hardware is done (

commandBuffer->waitUntilCompleted()).

After all this is done, the function exits. Because we specifically wait for the buffer to complete, we can see this as a blocking array operation. One could remove the waiting for the buffer, and additionally return the command buffer, such that the array operations can be performed asynchronously, and checked at a later time.

One obvious failing of this class and method in its original state was that the buffers themselves were linked to the class. To make our class more useful, we would like to pass the buffers, such that we can apply the operator to any arbitrary buffer defined elsewhere. Our class doesn’t change much functionally, other than accepting buffers and having a slightly clearer name.

void MetalOperations::addArrays(const MTL::Buffer *x_array,

const MTL::Buffer *y_array,

MTL::Buffer *r_array,

size_t arrayLength)

{

MTL::CommandBuffer *commandBuffer = _mCommandQueue->commandBuffer();

assert(commandBuffer != nullptr);

MTL::ComputeCommandEncoder *computeEncoder =

commandBuffer->computeCommandEncoder();

assert(computeEncoder != nullptr);

/// Encoding

/// ..omitted..

computeEncoder->endEncoding();

commandBuffer->commit();

// You could put this somewhere else, if you want asynchronous

// computations

commandBuffer->waitUntilCompleted();

}

Encode that operator

The compute method from our initial class (MetalAdder) called on another method to

encode the instructions and data, encodeAddCommand(). Other than taking care of the

instructions and data, it also computed in what shape to launch the kernel, something

possibly familiar to those who have seen CUDA:

void MetalAdder::encodeAddCommand(MTL::ComputeCommandEncoder *computeEncoder)

{

// Encode the pipeline state object and its parameters.

computeEncoder->setComputePipelineState(_mAddFunctionPSO);

// Place data in encoder

computeEncoder->setBuffer(_mBufferA, 0, 0);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(_mBufferB, 0, 1);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(_mBufferResult, 0, 2);

MTL::Size gridSize = MTL::Size::Make(arrayLength, 1, 1);

// Calculate a threadgroup size.

NS::UInteger threadGroupSize =

_mAddFunctionPSO->maxTotalThreadsPerThreadgroup();

if (threadGroupSize > arrayLength)

{

threadGroupSize = arrayLength;

}

MTL::Size threadgroupSize = MTL::Size::Make(threadGroupSize, 1, 1);

// Encode the compute command.

computeEncoder->dispatchThreads(gridSize, threadgroupSize);

}

After encoding the instructions (the pipeline of the add function) and data, this function does the following:

- Compute how many total processes need to be run (

gridSize). This is simply the length of our two arrays in this case. - Figure out how many processes the hardware could run at a time, by having a gander

at the pipeline:

_mAddFunctionPSO->maxTotalThreadsPerThreadgroup(). I guess it does realize that for some pipelines, this number varies based on shader properties. It stores this inthreadGroupSize. - If the array is shorter than the amount of threads that can be run at a time, reduce the size of the thread group.

- Encode the size of the grid and the thread group.

You might notice that the sizes in MTL have three entries. This is (I think) because MSL can natively handle up to 3 dimensional grids when performing computations on accelerator hardware. Accessing arrays in two or three dimensional fashing is sometimes faster. This can happen e.g. when neighbouring pixels in all three dimensions are required in the computation of the kernel, leading to memory access patterns that can be optimized by the software, similar to how CUDA works for higher dimensional data. Let’s leave this lie for another time!

To homogenize this functionality with our new class, we combine this and the previously discussed method into a single method:

void MetalOperations::addArrays(const MTL::Buffer *x_array,

const MTL::Buffer *y_array,

MTL::Buffer *r_array,

size_t arrayLength)

{

MTL::CommandBuffer *commandBuffer = _mCommandQueue->commandBuffer();

assert(commandBuffer != nullptr);

MTL::ComputeCommandEncoder *computeEncoder =

commandBuffer->computeCommandEncoder();

assert(computeEncoder != nullptr);

computeEncoder->setComputePipelineState(_mAddFunctionPSO);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(x_array, 0, 0);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(y_array, 0, 1);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(r_array, 0, 2);

MTL::Size gridSize = MTL::Size::Make(arrayLength, 1, 1);

NS::UInteger threadGroupSize =

_mAddFunctionPSO->maxTotalThreadsPerThreadgroup();

if (threadGroupSize > arrayLength)

{

threadGroupSize = arrayLength;

}

MTL::Size threadgroupSize = MTL::Size::Make(threadGroupSize, 1, 1);

computeEncoder->dispatchThreads(gridSize, threadgroupSize);

computeEncoder->endEncoding();

commandBuffer->commit();

commandBuffer->waitUntilCompleted();

}

All-in-all, our C++ code has now become pretty lean. We do create a new command buffer and encoder everytime we want to use the Metal hardware. Although I am not sure of the overhead of constructing these objects, the total runtime of the kernels is still much faster than that of the serial or OpenMP equivalents.

In fact, we can try to encode more operations into a single encoder and send them to the

same buffer, to get a feel for the induced overhead. Let’s try to chain an add_arrays

and an multiply_arrays shader together. I haven’t discussed the multiply_arrays

shader before, but its implementation can be found in the repo, and only differs from

our previous add_arrays shader by one symbol. Extrapolating our previous approach to

run one shader, we might end up with something like the following for two shaders:

// encoder and buffer created, grid size computed, beforehand

computeEncoder->setComputePipelineState(_mAddFunctionPSO);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(x_array, 0, 0);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(y_array, 0, 1);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(r_array, 0, 2);

computeEncoder->dispatchThreads(gridSize, threadgroupSize);

computeEncoder->endEncoding();

commandBuffer->commit();

commandBuffer->waitUntilCompleted();

computeEncoder->setComputePipelineState(_mMultiplyFunctionPSO);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(r_array, 0, 0);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(y_array, 0, 1);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(r_array, 0, 2);

computeEncoder->dispatchThreads(gridSize, threadgroupSize);

computeEncoder->endEncoding();

commandBuffer->commit();

commandBuffer->waitUntilCompleted();

This compiles just fine. However, upon running we encounter a segmentation fault trying

the second setComputePipelineState. This seems logical, because we specifically told

the encoder we were done encoding commands. Removing the first endEncoding yields the

following message just before aborting:

-[IOGPUMetalCommandBuffer validate]:200: failed assertion `commit command buffer with uncommitted encoder'

[1] 57876 abort ./benchmark.x

What we actually have to do, is encode the entire chain of pipelines and buffer operations, and only then end the encoding, and commit the buffer:

// encoder and buffer created, grid size computed, beforehand

size_t index = 102; // some random place in the array

std::cout << "Initial state" << std::endl;

std::cout << "x: " << x[index] << " y: "

<< y[index] << " r: "

<< r[index] << std::endl;

auto expected_result = (x[index] + y[index]) * y[index];

std::cout << "Formula: (x + y) * y" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Expected result: " << expected_result << std::endl;

computeEncoder->setComputePipelineState(_mAddFunctionPSO);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(x_array, 0, 0);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(y_array, 0, 1);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(r_array, 0, 2);

computeEncoder->dispatchThreads(gridSize, threadgroupSize);

std::cout << "Current result: " << r[index] << std::endl;

computeEncoder->setComputePipelineState(_mMultiplyFunctionPSO);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(r_array, 0, 0);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(y_array, 0, 1);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(r_array, 0, 2);

computeEncoder->dispatchThreads(gridSize, threadgroupSize);

std::cout << "Current result: " << r[index] << std::endl;

computeEncoder->endEncoding();

std::cout << "Current result: " << r[index] << std::endl;

commandBuffer->commit();

std::cout << "Current result: " << r[index] << std::endl;

commandBuffer->waitUntilCompleted();

std::cout << "Current result: " << r[index] << std::endl;

Output:

Initial state

x: 0.287212 y: 0.704251 r: 0

Formula: (x + y) * y

Expected result: 0.698239

Current result: 0

Current result: 0

Current result: 0

Current result: 0

Current result: 0.698239

We can see how the actual computation is only performed somewhere between commit

and waitUntilCompleted. This chaining of operators might seem arbitrary, but when

benchmarked against the serial use of the add_arrays and multiply_arrays shaders

a speedup of 5% was achieved (see chaining_operators.cpp, serial op:

4800.38ms +/- 57.3528ms, compound op: 4544.57ms +/- 30.7632ms), suggesting that for

complex computations optimizing out the overhead of constructing buffers, placing data

in them and encoding the instructions might be worthwile. However, compared to our CPU

performances both for serial and OpenMP code, the gain is marginal.

Code duplication hell

So far, we’ve now created two shaders. For these shaders, we’ve had to retrieve the function reference and its pipeline state object (PSO) in our class constructor, and whenever we launch a shader, we call again on the PSO to set the instructions and determine the threadGroupSize.

This way, when we grow our library in our metal code (contained for this write-up in

ops.metal), we will have to keep adding attributes to our class for the PSOs, and

a-priori know what functions we should load:

MetalOperations::MetalOperations(MTL::Device *device)

{

_mDevice = device;

NS::Error *error = nullptr;

auto filepath = NS::String::string("./ops.metallib",

NS::ASCIIStringEncoding);

MTL::Library *opLibrary = _mDevice->newLibrary(filepath, &error);

// Loading functions

auto str = NS::String::string("add_arrays", NS::ASCIIStringEncoding);

MTL::Function *addFunction = defaultLibrary->newFunction(str);

str = NS::String::string("multiply_arrays", NS::ASCIIStringEncoding);

MTL::Function *multiplyFunction = defaultLibrary->newFunction(str);

str = NS::String::string("saxpy", NS::ASCIIStringEncoding);

MTL::Function *saxpyFunction = defaultLibrary->newFunction(str);

// Loading PSOs

_mAddFunctionPSO =

_mDevice->newComputePipelineState(addFunction, &error);

_mMultiplyFunctionPSO =

_mDevice->newComputePipelineState(multiplyFunction, &error);

_mSaxpyFunctionPSO =

_mDevice->newComputePipelineState(saxpyFunction, &error);

// .. error handling

// .. other constructor operations

}

This ungodly work surely can be automated… And behold, one could simply determine all

names of the functions in a Metal library using MTL::Library::functionNames();. This

leads to a much leaner way to create PSOs for all functions:

MetalOperations::MetalOperations(MTL::Device *device)

{

_mDevice = device;

NS::Error *error = nullptr;

auto filepath = NS::String::string("./ops.metallib",

NS::ASCIIStringEncoding);

MTL::Library *opLibrary = _mDevice->newLibrary(filepath, &error);

// Get all function names

auto fnNames = opLibrary->functionNames();

for (size_t i = 0; i < fnNames->count(); i++)

{

auto name_nsstring = fnNames->object(i)->description();

auto name_utf8 = name_nsstring->utf8String();

// Load function into a map

functionMap[name_utf8] = opLibrary->newFunction(name_nsstring);

// Create pipeline from function

functionPipelineMap[name_utf8] =

_mDevice->newComputePipelineState(functionMap[name_utf8],

&error);

}

}

This creates a map of all pipelines, which we can look up by knowing their utf8 name.

This for example simplifies the calling of our add_arrays:

computeEncoder->setComputePipelineState(_m);

// becomes

computeEncoder->setComputePipelineState(functionPipelineMap["add_arrays"]);

However, this does not fully make all our shader calls from C++ redundant. Although the

add_arrays and multiply_arrays calls in C++ (addArrays and multiplyArrays) are

one-to-one duplicates other than the PSOs, this is only the case because they have the

same signature. This becomes evident when we create the SAXPY shader.

The SAXPY shader, single precision ax plus y, performs almost the same operation as

add_arrays. However, the addition of a constant changes the signature:

kernel void saxpy(device const float* a [[buffer(0)]],

device const float* X [[buffer(1)]],

device const float* Y [[buffer(2)]],

device float* result [[buffer(3)]],

uint index [[thread_position_in_grid]])

{

result[index] = (*a) * X[index] + Y[index];

}

We have now added another pointer to a (device) float; a. Additionally you might

notice a contrast from our previous shader implementations, that did not include the

[[buffer(*)]], this explicitly loads a variable from a specific place in the buffer,

as placed by our encoder.

For a better explanation of the buffer indices and other shader inputs, see

5.2.1 Locating Buffer, Texture, and Sampler Arguments(page 79) in theMetal-Shading-Language-Specification.pdfavailable here.

The change of our signature does mean that we have a different number of buffers to

place in our encoder, hence why one cannot reuse MetalOperations::addArrays for

MetalOperations::saxpy method:

void MetalOperations::saxpyArrays(const MTL::Buffer *alpha,

const MTL::Buffer *x_array,

const MTL::Buffer *y_array,

MTL::Buffer *r_array,

size_t arrayLength)

{

MTL::CommandBuffer *commandBuffer = _mCommandQueue->commandBuffer();

assert(commandBuffer != nullptr);

MTL::ComputeCommandEncoder *computeEncoder =

commandBuffer->computeCommandEncoder();

assert(computeEncoder != nullptr);

// --- unique code ---

computeEncoder->setComputePipelineState(functionPipelineMap["saxpy"]);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(alpha, 0, 0);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(x_array, 0, 1);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(y_array, 0, 2);

computeEncoder->setBuffer(r_array, 0, 3);

NS::UInteger threadGroupSize =

functionPipelineMap["saxpy"]->maxTotalThreadsPerThreadgroup();

// -------------------

if (threadGroupSize > arrayLength)

threadGroupSize = arrayLength;

MTL::Size threadgroupSize = MTL::Size::Make(threadGroupSize, 1, 1);

MTL::Size gridSize = MTL::Size::Make(arrayLength, 1, 1);

computeEncoder->dispatchThreads(gridSize, threadgroupSize);

computeEncoder->endEncoding();

commandBuffer->commit();

commandBuffer->waitUntilCompleted();

}

What remains can now be worked away into other functions. Since the only thing that changes is the buffers (and their count), as well as the function reference, we can abstract the actual shader away in the following way:

void MetalOperations::Blocking1D(std::vector<MTL::Buffer *> buffers,

size_t arrayLength,

const char *method)

{

MTL::CommandBuffer *commandBuffer = _mCommandQueue->commandBuffer();

assert(commandBuffer != nullptr);

MTL::ComputeCommandEncoder *computeEncoder =

commandBuffer->computeCommandEncoder();

assert(computeEncoder != nullptr);

// Unique code -> un-uniqued.

computeEncoder->setComputePipelineState(functionPipelineMap[method]);

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < buffers.size(); ++i)

{

computeEncoder->setBuffer(buffers[i], 0, i);

}

NS::UInteger threadGroupSize =

functionPipelineMap[method]->maxTotalThreadsPerThreadgroup();

if (threadGroupSize > arrayLength)

threadGroupSize = arrayLength;

MTL::Size threadgroupSize = MTL::Size::Make(threadGroupSize, 1, 1);

MTL::Size gridSize = MTL::Size::Make(arrayLength, 1, 1);

computeEncoder->dispatchThreads(gridSize, threadgroupSize);

computeEncoder->endEncoding();

commandBuffer->commit();

commandBuffer->waitUntilCompleted();

}

void MetalOperations::addArrays(MTL::Buffer *x_array,

MTL::Buffer *y_array,

MTL::Buffer *r_array,

size_t arrayLength)

{

std::vector<MTL::Buffer *> buffers = {x_array,

y_array,

r_array};

const char *method = "add_arrays";

Blocking1D(buffers, arrayLength, method);

}

Now, when the method one wants to call changes signature to include more or fewer buffers, this is already accommodated:

void MetalOperations::saxpyArrays(MTL::Buffer *alpha,

MTL::Buffer *x_array,

MTL::Buffer *y_array,

MTL::Buffer *r_array,

size_t arrayLength)

{

std::vector<MTL::Buffer *> buffers = {alpha,

x_array,

y_array,

r_array};

const char *method = "saxpy";

Blocking1D(buffers, arrayLength, method);

}

The only requirements of this approach is that the general design of the shader does not

fundamentally change; an element wise 1d operation that only accepts buffers as input.

Additionally, our approach required us to drop the const qualifier from some of our

buffers that we do not wish to modify. Heed!

Finite differencing

One of the staples of scientific computations (and especially solving PDEs) is computing derivatives. One of the standard numerical approaches to calculating a derivative on a grid of values (such as an array) is by using finite differences; i.e. manually computing the difference between neighbouring points, and using those to determine derivatives (of whatever order).

This computation in standard serial C++ code would look something like this:

void central_difference(const float *delta,

const float *x,

float *r,

size_t arrayLength)

{

for (unsigned long index = 0; index < arrayLength; index++)

{

r[index] = (x[index + 1] - x[index - 1]) / (2 * *delta);

}

}

By comparing our next (index + 1) and previous (index - 1) point, and dividing their

difference by their spacing (2 * delta), we obtain the first order (central)

derivative.

We have to take care though that at the beginning and at the end of our array we don’t go out of bounds. Hence we use in those cases an alternative formula:

void central_difference(const float *delta,

const float *x,

float *r,

size_t arrayLength)

{

for (unsigned long index = 0; index < arrayLength; index++)

{

if (index == 0)

{

r[index] = (x[index + 1] - x[index]) / *delta;

}

else if (index == arrayLength - 1)

{

r[index] = (x[index] - x[index - 1]) / (*delta);

}

else

{

r[index] = (x[index + 1] - x[index - 1]) / (2 * *delta);

}

}

}

These conditional statements alone are a reason that central differencing becomes a bit more expensive than your average operation, but they are essential to the correct computation of the derivatives.

We can easily modify our SAXPY shader to work as a central differencing shader:

kernel void central_difference(

device const float* delta [[buffer(0)]],

device const float* X [[buffer(1)]],

device float* result [[buffer(2)]],

uint index [[thread_position_in_grid]],

{

if (index == 0)

{

result[index] = (X[index + 1] - X[index]) / *delta;

}

else if (index == arrayLength - 1)

{

result[index] = (X[index] - X[index - 1]) / *delta;

}

else

{

result[index] = (X[index + 1] - X[index - 1]) / (2 * *delta);

}

}

Except, one issue appears now. We also have to pass to this function the arrayLength,

to ensure that our right-side boundary case is handled well. We could make an extra

buffer, and pass the array size as an argument, but this is rather inelegant. In MSL, we

can use properties just like [[thread_position_in_grid]] to obtain characteristics

about our current shader:

kernel void central_difference(

device const float* delta [[buffer(0)]],

device const float* X [[buffer(1)]],

device float* result [[buffer(2)]],

uint index [[thread_position_in_grid]],

uint arrayLength [[threads_per_grid]])

{

if (index == 0)

{

result[index] = (X[index + 1] - X[index]) / *delta;

}

else if (index == arrayLength - 1)

{

result[index] = (X[index] - X[index - 1]) / *delta;

}

else

{

result[index] = (X[index + 1] - X[index - 1]) / (2 * *delta);

}

}

This [[threads_per_grid]] is exactly the size we passed using dispatchGrid in our

Blocking1D method, ideal for stencil operations. There is a few more descriptors that

can be accessed in this way. More information about launching shaders and how threads

behave can be found here

and here.

SAXPY and FD: GPU territory

In the previous write-up we saw how MSL + C++ can outperform C++ OpenMP code for adding arrays, a relatively simple operation. The speed-up of optimal OpenMP w.r.t. serial code was about x1.8, while the MSL shader performed the same oepration with a x3 speed-up.

We do the same profiling test on the SAXPY and the central differencing shader. In the

project’s repo, one can find the verification of the results (compared to CPU serial

code) and the benchmark itself in 02-GeneralArrayOperations/main.cpp. The general idea

behind the compilation can be read

here, but if you are using VSCode,

the .vscode/tasks.json should contain all the details you need.

The benchmark has an output on my 2021 MacBook like this:

Running on Apple M1 Max

Array size 67108864, tests repeated 1000 times

Available Metal functions in 'ops.metallib':

central_difference

saxpy

multiply_arrays

add_arrays

Add result is equal to CPU code

Multiply result is equal to CPU code

SAXPY result is equal to CPU code

Central difference result is equal to CPU code

Starting SAXPY benchmarking ...

Metal (GPU): 2413.85ms +/- 75.9983ms <-- 4.1x speed-up

Serial: 9887.88ms +/- 520.411ms

OpenMP (2 threads): 5628.79ms +/- 1039.63ms

OpenMP (3 threads): 6863.52ms +/- 504.79ms

OpenMP (4 threads): 5781.61ms +/- 702.583ms

OpenMP (5 threads): 6178.79ms +/- 224.011ms

OpenMP (6 threads): 5530.03ms +/- 465.312ms

OpenMP (7 threads): 5888.13ms +/- 309.846ms

OpenMP (8 threads): 5350.56ms +/- 68.6307ms

OpenMP (9 threads): 5284.93ms +/- 442.001ms

OpenMP (10 threads): 5248.47ms +/- 482.052ms <-- 1.8x speed-up

OpenMP (11 threads): 6092.41ms +/- 1162.83ms

OpenMP (12 threads): 7914.33ms +/- 1680.73ms

OpenMP (13 threads): 8611.03ms +/- 1653.91ms

OpenMP (14 threads): 6918.88ms +/- 1769ms

Starting central differencing benchmarking ...

Metal (GPU): 1707.02ms +/- 639.27ms <-- 27x speed-up!

Serial: 46894.8ms +/- 214.954ms

OpenMP (2 threads): 29274.6ms +/- 84.4059ms

OpenMP (3 threads): 22267.3ms +/- 166.856ms

OpenMP (4 threads): 18256.5ms +/- 142.291ms

OpenMP (5 threads): 14330.1ms +/- 492.599ms

OpenMP (6 threads): 11894.4ms +/- 858.88ms

OpenMP (7 threads): 11110.7ms +/- 1751.74ms

OpenMP (8 threads): 9877.14ms +/- 746.775ms <-- 4.7x speed-up

OpenMP (9 threads): 10826.8ms +/- 1344.18ms

OpenMP (10 threads): 10408.7ms +/- 1113.99ms

OpenMP (11 threads): 11120ms +/- 1408.25ms

OpenMP (12 threads): 11427.5ms +/- 1347.53ms

OpenMP (13 threads): 11707.8ms +/- 1734.43ms

OpenMP (14 threads): 11301.5ms +/- 1929.12ms

The great thing is that the Metal GPU outperforms OpenMP across the board. The speed-up of the central differencing kernel is remarkable, 27x w.r.t. the serial code, with the OpenMP implementation not getting close at all. For SAXPY the GPU is 2 times faster than all CPU cores, for central differencing it is more than 5 times faster!

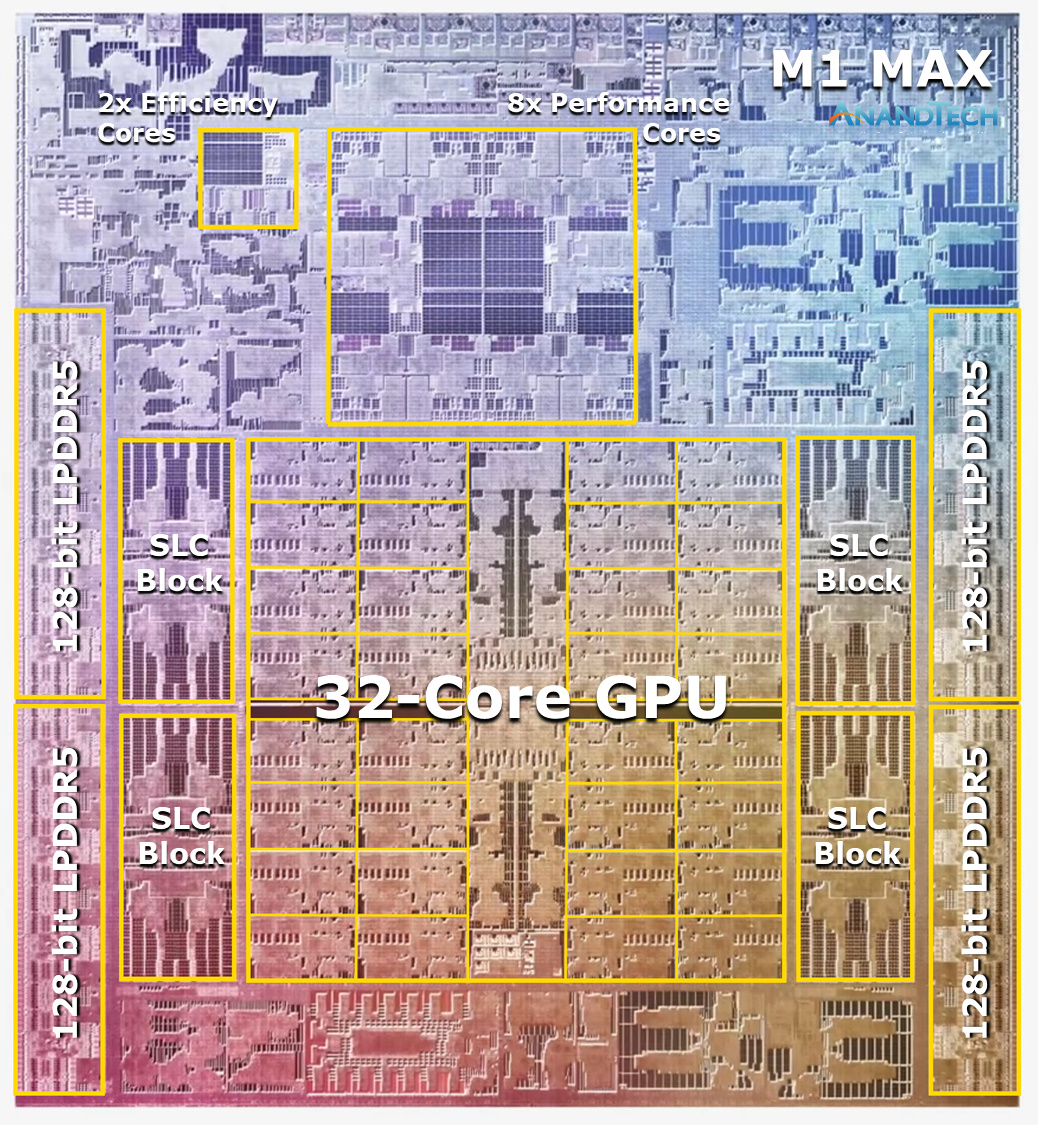

Additionally, it is interesting to see at which thread count the OpenMP code performs best. The M1 max chip has 10 cores, of which 2 are ‘efficiency’, and the rest ‘performance’. In the addition test, a relatively simple kernel, OpenMP performance peaked at 2 threads. Now we see OpenMP perform best at a much more expected place: at 10 cores for SAXPY, and 8 cores for central differencing. I suspect that in these computationally heavier shaders the computational benefit outweighs inefficient memory access patterns or bandwidth saturation.

I highly suspect the slowdown between 8 and 10 threads on OpenMP central differencing to be due to the threads running on the efficiency cores: when the threads need to access buffers at indices, they actually have to communicate with memory addresses close to the performance cores, as illustrated in the above diagram. This process likely slows down the entire operation.

Next work will be on 2 dimensional shaders, which I have high hopes for!